The present aim is to describe Alberti’s architectural activity beyond the strict limits of his building practice. It is a sort of borderland that is to be explored, where boundaries of all sorts are uncertain, provisional and porous. Is the prospect then of a featureless and limitless heathland? No: rather the view is of winding and intersecting paths and sudden long perspectives. It is a landscape of exploration and discovery.

First of all, the boundary that is represented by death itself is of a paradoxical character. For the observer, the chronological limits of a life are not finite. Fame transgresses them. So, in the spirit of enquiry into what is beyond, and as a preparatory exercise so-to-speak in tracing the imprecise, there calls to be described Alberti’s late-fifteenth-century ghost –a shape elusive, consisting in the vague contours of perhaps imperfect memory, through the distortions of misinformation and the pragmatism of tendentiousness.

The reliability of posthumous witnesses to the life of Alberti is not guaranteed; but their evidence calls to be evaluated. An attempt to describe his post-mortem existence in the first decades after 1472 could be useful. Certainly, it adds to the data that may be of relevance for an understanding of his life and work. The conditional and subjunctive voices must be recurrent in this sort of enquiry, and the reader remains the judge.

Alberti’s writings and therefore his thinking on architecture continued to be of interest. Clearest evidence is in the fact that De re aedificatoria was published in Florence in 1485. A printed version of Vitruvius did not appear until 1486.[1]

Equally indicative, we may believe, of the influence of Alberti on architectural thinking is a thread of commentary that passes through Antonio Manetti’s Life of Brunelleschi.[2] If something was irking Manetti –for the tone is sometimes resentful and querulous– it was surely not Alberti’s architecture itself of which he was critical, for that could have no deleterious effect upon the reputation of the work of his subject, Brunelleschi. A consideration of the argument and of the motivation for its insertion leads to the proposition that Manetti’s biography was, in a perverse way, a hidden obituary of Alberti; prompted in part by the reputation that he had left behind.[3] Perhaps Manetti had got wind of plans to publish De re aedificatoria, and he feared the pre-eminence that it would claim for the author.

Equally galling might have been the claims of Cristoforo Landino who, in his Apologia di Dante, published in 1481, commemorated Alberti’s skills:

Where is Alberti to be found, or in what category of the learned shall I put him? You will say, among the natural scientists. And indeed I assert that he was born precisely to investigate the secrets of Nature. What branch of mathematics was unknown to him? He was a geometer, arithmetician, astronomer, musician, and in perspective he was a prodigy, greater than anyone over the centuries.‘ Landino goes on to praise Alberti’s practical and theoretical accomplishment in the visual arts, before turning to the Trivium and addressing his literary style: ‘Like a cameleon he appeared, always adapting to the hue of the matter that he wrote about.’[4] He contributed, Landino continues, to the development of the Italian language, in the tradition of Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio and Fazio degli Uberti and ‘in prose has outstretched and surpassed all his predecessors.[5]

The appearance, in 1480, of the Disputationes Camaldulenses, in book I of which Alberti had a prominent role in discussion with Lorenzo de’ Medici may also have irked Manetti.

Filarete, in Book II of his Trattati, written in the early 1460s, anticipated Landino in the general drift of his mention of ‘Battista Alberti il quale a questi nostri tempi, uomo dottissimo in più facultà, è in questa molto perito, massime nel disegno, il quale è fondamento e via di ogni arte che di mano si faccia. E questo lui intende ottimamente in geometria ed altre scienze è intendentissimo; lui ancora ha fatto in latino opera elegantissima.’[6]

Angelo Poliziano, in his dedication of De re aedificatoria to Lorenzo de’ Medici wrote,

Surely there was no field of knowledge however remote, no discipline however arcane, that escaped his attention; you might have asked yourself whether he was more an orator than a poet, whether his style was more majestic or graceful. So thorough had been his examination of the remains of antiquity that he was able to grasp every principle of ancient architecture, and knew it by example; his invention was not limited to machinery, lifts and automata, but also included the wonderful forms of buildings. He had moreover the highest reputation as both painter and sculptor, and since he achieved a greater mastery in all these different arts than only a few can manage in any single one, it would be more telling, as Sallust said about Carthage, to be silent about him than to say little.[7]

Poliziano surely intends his reader to smile at his own disregard of Sallust’s rule, for the encomium seems comprehensive.

Alberti receives only one direct mention in the Life of Brunelleschi. The general polemic of the biography, however, can be argued to contain an attempt to rectify what was, for Manetti, a false conception of the history of architecture in fifteenth-century Florence and, in place of Alberti, to reinstate Brunelleschi as its true father.

Manetti is at pains to establish Brunelleschi as the first archaeologist of ancient Roman architecture. He and Donatello –who, Manetti insists, did not understand his associate’s purposes and analyses– hired labour and made excavations:

No one else attempted such work or understood why they did it. This lack of understanding was due to the fact that during that period, and for hundreds of years before, no one paid attention to the classical method of building: if certain writers in pagan times gave precepts about that method, as Battista degli Alberti has done in our period, they were not much more than generalities. However, the invenzioni – those things peculiar to the master – were in large part the product of empirical investigation or of his own [theoretical] efforts.[8]

Manetti is, in effect, accusing Alberti of superficiality as a student of ancient architecture: he has located himself in a literary tradition, but has neglected to look closely at the material relics. The latter tell a different story. From ancient writings come general rules, but no insight into the art. The student of individual buildings deals not with generalities, and there discovers not the formulaic but the creativity of the architect himself. Alberti (unlike Brunelleschi) was cut off from the possibility of making such discoveries. The translation of the final sentence of the passage does not catch Manetti’s point. Earlier on, in the discussion of Brunelleschi’s invention of the one-point perspective system, he had set up an opposition between industry and intelligence, connecting them with invention and rediscovery. He wrote, ‘Ma la sua industria e sottiglieza o ella la ritrovo o ella ne fu inventrice.’[9] By repeating ‘o ella’ the writer lays a choice before the reader. A bald translation would be, ‘Either his industry rediscovered it or his ingenuity invented it.’ The reader is to decide which is the writer’s preference. The later passage, lacking the symmetry of the earlier, allows for both wit and application in the production of innovation. By transferring the passage into the indicative voice, the translator removes a note of insistence that is present. Manetti is drawing a distinction between what masters and those lacking mastery are capable of: ‘…bisognia che … sieno…’ A paraphrastic translation would be: ‘But it is necessary that inventions, which are things belonging specifically to mastery, should largely be gifts of nature or [to a lesser degree the product] of individual industry.’ The clear implication is that Alberti’s contribution is founded on neither wit nor industry and does not lead to fresh achievement. Of course, the battle is being fought on paper: Manetti would be hard-pressed to make the point before Alberti’s actual buildings.

Throughout the Life there are scores being settled. Ghiberti, Donatello, Francesco della Luna –Brunelleschi’s fellow architectural amateur and member of the Silk Merchants Guild– and Antonio Ciaccheri Manetti, his model-maker, are fingered, for thwarting, misunderstanding and betraying Brunelleschi’s purposes. Classical architectural solecisms in Brunelleschi’s buildings are, in other words, to be blamed on others. But there are also more elusive and perhaps insidious threats to Brunelleschi’s fame; after his death, damage continues to be done.

In emphasizing Brunelleschi’s precocity as an investigator of Roman remains, Manetti claims for him an expertise the lack of which would, in fact, do him no discredit, given that the achievement of a rational classicism at such an early time on the basis of a very limited understanding of material classicism would be admirable enough. Special pleading is necessary, given the relative sophistication of the 1480s view upon classical architecture. Manetti is reaching beyond simple encomium here. In addition, the need to insist upon Brunelleschi’s having reconstructed the orders, when there is no evidence of him having done much more than recognise the Corinthian and Ionic, is also a sign that Manetti’s purpose was not so much to praise his subject as to advance a claim against opposition. Among that opposition to the reputation of Brunelleschi was –it can be argued– the fame of Alberti.

Repeatedly, in the biography, Brunelleschi out-Alberti’s Alberti. An emphasis in the Life which is slightly surprising is on Brunelleschi’s activities as an architectural advisor. He is consulted by princes.[10] In itself, the emphasis cannot be particularly fruitful because, by its nature, advice leaves little trace in the form of surviving material evidence to honour its source; and Brunelleschi’s merits remain elusive. What does emerge is the implication that Brunelleschi’s influence was strategic; his shaping of architectural understanding happening at the highest social and most politically-effective levels. Now, Alberti seems to be rivalled in this. Whilst, nowadays, the influence of Alberti’s built work and of his treatise on architecture, De re aedificatoria, seem most noteworthy, it was perhaps not always the case. Alberti’s activity as an advisor could have been particularly prominent. He was a formative influence on the thinking of princes, as peripatetic architectural advisor. And there are important projects which almost certainly received Alberti’s contribution at the planning stage. The hard evidence has, of course, eroded with the passage of time. But, closer to events, it could have seemed that no pie was without Alberti’s finger in it. It was important that Brunelleschi should influence by his ideas as well as by his built work.

In view of Alberti’s expertise and his publicly-indicated desire and his opportunity to shape the thinking and practice of architecture in Rome, Florence and the princely courts, it is scarcely conceivable –no matter, silence in the documentation– that he did not serve in an advisory role in the formulation of the plans of Nicholas V and Pius II for Rome and Pienza. His activities at Rimini, Ferrara, Urbino and Mantua –and no doubt elsewhere– would have been well-known. It could have seemed a relentless omnipresence. This is not the place to enlarge upon the point in detail: that will be done below. But the Benediction Loggia and the systematisation of the approach to St Peter’s under Pius II are consistent with Alberti’s thinking about how clergy and laity should relate. The portico and loggia of S. Marco, part of the insula of the Palazzo Venezia, bears a strong resemblance to the Benediction Loggia. Alberti presented De re aedificatoria, substantially complete, to his friend Nicholas V in 1452. He had begun ‘…que’ miei libri de architettura, quale io scrissi richiesto dall’ Illustrissimo [Leonello d’Este]’ who died in 1450, so the text was not conceived and was probably not largely written with the repair of Rome in mind.[11] That said, however, is it possible that Alberti sought no part in the laying of Nicholas’s plans for the re-instatement of Rome and the Vatican within Christendom and, perhaps, in her own pre-Christian history? No discussion of Pienza will exclude debate about Alberti’s advisory presence, either in relation to the planning of some of the architectural elements (though not the façade of the cathedral whose grasp of the classical grammar is so weak as to fail the most unexacting test that Alberti could have set, and indicates the remoteness of his involvement with that part of the project) or in relation to the urbanistic concept as a whole.

Through De re aedificatoria, Alberti sought to influence architectural thinking at the level of philosophy and policy –well before an actual building and its form would emerge for consideration. Manetti’s undermining of that activity as mere generalisation has the effect of preserving for Brunelleschi the prime strategic and historical position within the classical-architectural revival. In addition, Manetti insists upon Brunelleschi’s cogency and fluency as an advisor. His oral explanation of the dome project was much fuller than the text of the memorandum that he prepared.[12] Manetti continues: ‘He explained the matter orally much more clearly and fully than he had done in the written account for those who asked and were interested and could comprehend it. He did it in such a way that many, admiringly, became quite expert about it. As a consequence he achieved great renown and confidence. His marvelous genius were[?] proclaimed everywhere’.[13] This is reportage or fabulation, for Manetti was a boy during the period of construction of the dome. In either case, it must conceal a polemic. Brunelleschi was also an able informal educator.[14] With such skills as a communicator, he measures himself against any pedagogue. And if one teacher published no better than commonplaces, so much was Brunelleschi’s educative merit superior.

Howard Saalman observes that Manetti’s excursus into the history of architecture is indebted to Alberti’s.[15] If so, his deviations from Alberti’s account amount to contradictions. The main difference between the two arguments is that Manetti’s history traces materialist changes more than does Alberti’s. Bitumen, brick, stone and timber are important factors in his narrative. Alberti tells a more philosophically-directed story. Architecture’s beginnings in Egypt and then Assyria were materialist, and progress consisted in crude increase in size and richness. The Greeks, by contrast, made an austere and frugal architecture whose merit consisted in the rigour of its mathematics –an abstract content. Alberti had introduced his brief history with a very strong metaphor. Like an organic thing, architecture had grown, flourished and come to maturity: ‘Aedificatoria, quantum ex veterum monumentis percipimus, primam adolescentiae, ut sit loquar, luxuriem profudit in Asia; mox apud Graecos floruit; postremo probatissimam adepta est maturitatem in Italia.’[16] The teleology is so insistent that it is easy to overlook the actual antithesis that Alberti set up between Asia and Greece, but, when noticed, it is difficult to resist the notion of a Hegelian sort of synthesis. At last, with the Romans, a development was complete and the reconciliation of an opposition was achieved: the wealth of the Romans enabled them to build copiously and sumptuously; but they never fell into Asiatic excess. For in their recollection of their own republican frugality, together with the intellectual debt that they owed to the Greeks, they always gave to their building a core of probity and intellectual seriousness.[17] If as Alberti said, architecture should be a meeting of form and matter, Rome’s architecture was best. A more materialistic history, on the other hand, would perhaps better find its apogee in an architect lauded for his outstanding practical gifts –a Daedelean figure, like Manetti’s subject as he was celebrated in Florence Cathedral.

Manetti also knew Alberti’s treatise on painting. It was surely Landino’s knowledge of that text that encouraged him to claim for Alberti preeminence as a perspectivalist. The text surely threatened to cast Brunelleschi, the perspectivalist, into oblivion, for Landino’s words dismiss rivals: ‘in perspective he was a prodigy, greater than anyone over the centuries.’ Manetti’s account of Brunelleschi’s invention of the one-point perspective system concludes on the point that his achievement owed nothing to the ancients: ‘We do not know whether centuries ago the ancient painters … knew about perspective or employed it rationally. If indeed they employed it by rule … as he did later, whoever could have imparted it to him had been dead for centuries and no written records about it have been discovered, or if they have been, have not been comprehended. Through industry and intelligence he either rediscovered or invented it.’[18] Alberti, in the prologue to Della pittura, had also praised Brunelleschi on his independence of ancient precept, but in relation to the Florence Cathedral dome project. In the treatise, Alberti had gone on to offer a perspective procedure for painters, making no mention of Brunelleschi as the forefather of the method. By asserting Brunelleschi’s independence of precedent in relation to the perspective method, Manetti was, in effect or deliberately, undermining Alberti’s authority as an original voice within the pages of Della Pittura and as the one advanced by Landino. Manetti returned to the matter of uninstructed invention. This time he re-established Brunelleschi as an innovator in his achievement of the dome: ‘He saw and reflected on the many beautiful things, which as far as is known had not been present in other masters from ancient times.’[19] Manetti seems also to hint that Brunelleschi’s perspective method germinated in his surveying of the ruins of ancient Rome.[20]

On several occasions, Alberti claimed to be acting independently of precedent. In making the claim, he was, for Manetti, rivalling the exemplary innovator of the age, Brunelleschi. Alberti did not regard the classical architectural orders as definitive in number and form. [This point is elaborated later on. Might the point be made more briefly here?] New orders could be invented: ‘…non quo eorum descriptionibus transferendis nostrum in opus quasi astricti legibus hereamus, sed quo inde admoniti novis nos proferendis inventis contendamus parem illis maioremve, si queat, fructum laudis assequie.’[21] He believed that he was treating new material in De pictura: ‘…et a nemine quod viderim alio tradita litteris materia…’[22] In writing about colour, he had no fount of wisdom to draw on: ‘ferunt Euphranorem priscum pictorem de coloribus nonnihil mandasse literis. Ea scripta non extant hac tempestate. Nos autem qui hanc picturae artem seu ab aliis olim descriptam ab inferis repetitam in lucem restituimus, sive nunquam a quoquam tractatam a superis deduximus, nostro ut usque fecimus ingenio, pro instituto rem prosequamur.’[23] At last, he felt himself able to claim, ‘Nos tamen hanc palmam praeripuisse ad voluptatem ducimus, quandoquidem primi fuerrimus qui hanc artem subtilissimam literis mandaverimus.’[24] On other occasions, Alberti made similar claims. [Take the stuff below and integrate it into Section 14. In De equo animante, he states that he has things to say about horses’ illnesses that were unremarked by the ancients.[25] At the beginning of Book II of De famiglia, Leon Battista addresses Lionardo and praises his way of thinking – different in character from that of the ancient authors.[26] Adovardo, in Book IV does not bow to the authority of the ancients on the matter of amicizia: ‘Ma parmi in questa materia già fra me non so che piú desiderarvi altro filo e testura, in quale né degli antichi ancora scrittori alcuno apieno mi satisfece.’[27] He notes that it was a topic not much treated by the ancients and doubts if the general reader would find much to praise in what they did write.[28] It is with false modesty that, before Lionardo, he disclaims the possibility that he should have been able to come up with original ideas about amicizia: ‘Ma divolgarete voi in publico ch’io uomo ingegnosissimo trovai nuove e non prima scritte amicizie?’[29] There is no such modesty when Adovardo comes to laying out the rule for how to avoid envy: ‘cosa utilissima e forse non altrove udita.’[30]]

What emerges from these passages is Alberti’s belief that he has made discoveries, inventions and unprecedented observations. Manetti, in the biography, made sure that Brunelleschi had first claim on the title of inventor.

[Shift this too. Alberti’s Intercenale, ‘Annuli’ is about making new things. Pebbles are to be got from the fountain (the history of letters). So is golden sand. Philoponius casts it into rings and inscribes them. The idea is that the aggregate is changed into the artist’s own work. His work is not just a polishing of works already made.]

——

So much for reputation. What of material signs of Alberti’s postumous influence? Manetti’s enmity, though of a debatable depth, is sufficiently demonstrated to establish that Alberti’s influence upon architectural thinking survived his death. De re aedificatoria, evidently, continued to shape or affect thinking. The treatise, as well as being a manual of instruction, carried a polemic, the outlines of which are to be discerned dimly nowadays, and were, no doubt, clearer to see closer to Alberti’s time.[31] Were Albertian buildings rising in the years after his death?

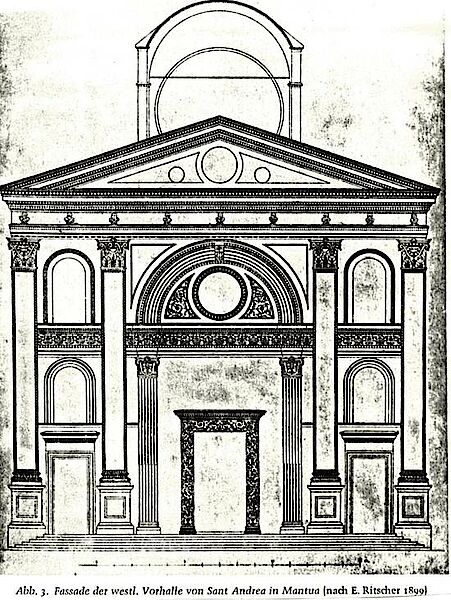

There is a dictum that seems to stand at the very centre of Alberti’s thinking about church architecture, and seems by turn to have been transformed into a pattern for churches in the following decades. The argument was reduced to its essence in this; a divide existed between pastor and priest and between a faithful committed to one another and to their individual salvation. The church, reduced to its core elements, consisted of a congregational space and a sacramental one: ‘All temples consist of a portico and, on the inside, a cella….’[32] They stand in a certain dialectical relation. And that relation seems to inform his thinking about the church building itself. The Romans bequeathed to Christian tradition the temple and the basilica. The one had, at its core, an arcane and sacramental religion. The other served congregational purposes. As a place of assembly adjacent to the public realm, it had something of the portico about it. Another difference between the two religious buildings was that the temple would be vaulted and the basilica be timber-roofed. Alberti employed this dualism to aid archaeological speculation when he came to discussing the curia in De re aedificatoria.[33] It was evidently an instrument for discriminating between categories. He confessed to having little direct knowledge of the building type where public speech is to take place; but he conjectured that there would be a religious curia and a secular one. The difference would be that the one would associate itself with the form of the temple, and the other, of the basilica. So, the religious curia would be vaulted and the secular one would be timber-ceiled. The Tempio Malatestiano, as represented in Matteo de’Pasti’s medal, and Santissima Annunziata, with which Alberti was associated, combine these basic characteristics of the templum and basilica. Other churches, do not conjoin vaulted and timber-roofed structures but do combine the sacramental space and the congregational in an approximation to the contrast that Alberti has in mind in De re aedificatoria.

Several churches were built around the time of the pontificate of Sixtus IV. They diverge from traditional functional compositions but are true to the basic bi-partite division that Alberti proposed. It is possible that Alberti’s advice echoed in the minds of their builders. The church of S. Maria della Pace (1478-83) is, in its general functional composition, close to S. Pietro in Montorio (1472-80). A nave with side-chapels carved out of the thickness of the wall, which is massive enough support for vaulting, gives onto an open sacramental place. Chapels were also a by-product of vault-buttressing –to even more Roman effect– at Sant’ Andrea in Mantua. At S. Pietro in Montorio, the crossing which comes immediately before the sacramental place gives directly onto apsidal chapels. The activity of these chapels almost jostles with witness to the ritual of the high altar. In the case of S. Maria della Pace, this space is sufficiently integrated with the nave that it too has chapels. The arrangement is not very different from that at the rotunda of Santissima Annunziata in Florence, a building that, if it was not designed by Alberti, was praised by him.[34] There, too, traffic to chapels around the domed space threatened, according to critics of the scheme, the composure of the clergy. The result is that the notion of sanctuary is compromised.

Around 1472 [?], there was a controversy in Florence about the form that the church of SS. Annunziata should take. A rotunda with chapels, which seems to have been begun by Michelozzo in the late 40s at the east end, was in process of modification and completion. Funds owing to the Marquis of Mantua, Lodovico Gonzaga, were supporting the campaign. Objectors to the rotunda proposed instead that an arrangement of major chapel and flanking secondary chapels –familiar in Florence in such churches as S. Croce, S. Maria Novella and S. Trinità– be substituted. Lodovico was irked to be importuned in this way. At the same time, Alberti’s support for the rotunda was cited. [quote]

Lodovico and Alberti prevailed. Perhaps Antonio Manetti recalled this skirmish. The plan that failed to convince was favoured not just by convention and arguments of convenience in Florence, but also by Brunelleschi himself, at S. Lorenzo. It would be possible to construe from the episode the threat of an eclipse.

[VIII,9 contains Alberti’s description of the Curia Pontifica. It resembles what was built later by Sixtus V as the Sistine Chapel (Borsi, p.38) I don’t see it myself particularly. I note that there were two curias. Alberti speculates upon their differences. The secular one he would have timber-roofed and the religious one vaulted, imagining that something of the temple would be appropriate to the latter and something of the basilica to the former. Of course, the church is a hybrid of temple and basilica, sacred and (relatively) profane, cella and portico.]

Alberti’s ideas probably also resonated in Sixtus’s plan for the city of Rome as a whole. They were surely influential in Nicholas’s five-point plan as described by Giannozzo Manetti. Sixtus, an architecturally very ambitious pope, worked largely within the framework that Nicholas had proposed.

Alberti’s spirit, along with Plutarch’s, was also present on 18th April 1506. On this auspicious day, the New St Peter’s was begun The inscription on Caradosso’s Medal marking the occasion is TEMPLI PETRI INSTAURACIO. Alberti wrote in De re aedificatoria that the augurs predicted that Rome would become mistress of the world because a man born on the day of her foundation would become king: ‘Hunc invenio fuisse Numam; nam conditam urbem et natum Numam ante diem XIII kalendas Maias meninit Plutarchus.’ (IV,3, p,293) The day is 19th April. The choice of 18th April for the laying of the foundation stone of New St Peter’s seems to acknowledge in some way the anniversary of the following day. Numa might have a part, but the day a.u.c. certainly does.

Another history of architecture of sorts in Deifira:

Filarco

Pallimacro, nella vita de’ mortali nulla si truova a chi non stia apparecchiato il suo fine. Troia fu grande e alta, Babillonia fu ricca e possente, furono Atene ornatissime e famosissime, e Roma fu temuta, riverita e ubbidita, quanto tempo il cielo e sua sorte a ciascuna permise.

[1] Of course, fame can benefit from promotion. Alberti had, so-to-speak, a sponsor. As Poliziano says in the dedication, Bernardino Alberti, his cousin, was instrumental in publishing the treatise. It would be a more disinterested scholarship that would promote the publication of an ancient Roman’s work.

[2] Howard Saalman (The Life of Brunelleschi, by Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, Introduction, Notes and Critical Text edition by Howard Saalman, translation by Catherine Engass, The Pennsylvania State University Press: University Park and London, 1970) describes Alberti’s influence on Manetti’s Life of Brunelleschi as ‘profound’, and suggests the possibility, discussed further below, that Brunelleschi’s conducting of archaeological investigations in Rome was a fabrication by Manetti to give Brunelleschi the credentials necessary for architectural respectability in the second half of the fifteenth century. (p.29) Otherwise, Saalman’s discussion of the Life as a critique of Alberti’s theory and practice depends upon a somewhat caricatured account of the latter.

[3] Saalman dates the Life between 1497 (the death of Antonio Manetti in whose hand the oldest of the manuscript texts is written) and 1482 (the death of Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (who is referred to in the past tense). By more circumstantial argument he arrives at a likely terminus anti quem of 1489.(pp.10-11). It may be remarked that the passage referring to Toscanelli is clearly an interpolation It postpones Manetti’s promised treatment of the question of the origins and development of architecture whilst adding nothing to the immediate argument. However, there is no way of knowing when the passage was inserted and it is not possible to hypothesise its addition to a text first prepared before Toscanelli’s death.

[4] Comento di Christoforo Landino Fiorentino sopra La Comedia di Danthe Alighieri poeta fiorentino (‘Fiorentini eccellenti in dottrina’): ‘Ma dove lascio Baptista Alberti, o in che generatione di docti lo ripongo? Dirai tra’ physici. Certo affermo lui esser nato solo per investigare e secreti della natura. Ma quale spetie di mathematica gli fu incognita? Lui geometra. Lui arithmetico. Lui astrologo. Lui musico, et nella prospectiva maraviglioso più che huomo di molti secoli. Le quali tutte doctrine quanto in lui risplendessino manifesto lo dimostrono nove libri De architectura da llui divinissimamente scripti, e quali sono referti d’ogni doctrina, et illustrati di somma eloquentia. Scripse De pictura. Scripse De sculptura, el qual libro è intitolato Statua. Nè solamente scripse, ma di mano propria fece, et restano nelle mani nostre commendatissime opere di pennello, di scalpello, di bulino, et di gecto da llui facte.[get] [check: there’s a problem with the cameleon ref. I seem to have the wrong source in Landino. Check Mancini, below] It is possible that, in likening Alberti to a cameleon, he was intending his reader to take up a hint that he was the Alcibiades of the liberal arts. Alberti himself referred frequently to Alcibiades ability to adapt to differing circumstances and, in Book IV of De familia noted his cameleon character (Furlan, p.420, lines 2621-3).

[5] See Girolamo Mancini, Vita di Leon Battista Alberti, Roma, Bardi Editori, 1971, p.442: ‘ Dove lascio Battista Alberti o in che generatione di dotti lo ripongo? Dirai tra’ fisici; certo affermo lui esser nato per investigare e segreti della natura. Ma quale spetie di matematica gli fu incognita? Lui geometra, lui aritmetico. Lui astrologo, lui musico, et nella prospettiva maraviglioso più che huomo di molti secoli … come nuovo camaleonta sempre quello colore piglia, il quale è nella cosa, della quale scrive …in prosa ha avanzato et vinto tutti i superiori.’ [see note above –disparity]

[6] Antonio Averlino (Filarete), Trattato di Architettura, facsimile p.42 [get]

[7] Rykwert et al, p.1; Orlandi, L’Architettura, p.3. ‘Nullae quippe hunc hominem latuerunt quamlibet remotae litterae, quamlibet reconditae disciplinae. Dubitare possis, utrum ad oratiam magis an ad poeticam factus, utrum gravior ille sermo fuerit an urbanior. Ita perscrutatus antiquitatis vestigia est, ut omnem veterum architectandi rationem et deprehenderit et I exemplum revocxaverit; sic ut non solum machinas et pegmata automataque permulta, sed formas quoque aedificiorum admirabilis excogitaverit. Optimus praeterea et pictor et statuarius est habitus, cum tamen interim ita examussim teneret omnia, ut vix pauci singula. Quare ego de illo, ut de Carthagine Sallustius, tacere satius puto quam pauca dicere.’

[8] Manetti, p.54. The Italian is as follows: ‘E la cagione del non estimare el perche era, perche in quel tenpo non era chi atendessi, ne era stato di centinaia d’anni innanzi chi auessi ateso al modo dello edificare antico; del quale se per alcuno autore nel tenp de gentilj se dato precetto, come ne nostrj di fecie Batista degli Alberti, poco si puo altro che delle chose generalj; ma le invenzione, che sono cose proprie del maestro, bisognia, che nella maggiore parte sieno date dalla natura o dalla industria sua propria.(p.55, l.380-86)

[9] Manetti, p.43, l.156-57

[10] lines 110, 530, 1050

[11] Alberti, Ludi Rerum Mathematicarum, in Opere Volgari a cura di Cecil Grayson, Vol.III, Bari, Laterza, p.156

[12] Manetti, lines.698-762

[13] Manetti. p.76, l.766-771: ‘…e molto piu chiaramente e piu largo dicieva le cose a boccha a chi nel dimandaua, che n’ auessi qualche interesso e fussi atto a ricieuerlo, che non aueua dato per iscritto, per modo che in buona parte molti con amiratione pero ne furono capacj assaj; di che egli aquisto gradissima riputatione e fede, e predicauasi per tutto el marauiglioso ingiegnio e inteletto.’.

[14] Manetti, p.43, lines 164-66:’… et insegniaua uolentierj acchi gli pareua, che lo disiderassi effusi atto a ricieruerlo.’

[15] Manetti, p.29. l.421-530: cf. Alberti De re aedificatoria, VI, 3

[16] Alberti, loc.cit., p.451

[17] It is unlikely that Alberti intended the reader to look for a modern exemplification of the contrast between Roman probity and Asiatic excess, but a comparison of the Palazzo Medici and the Palazzo would have found scale and mass in the one and, in the other, those qualities reined in by the severe discipline of the orders.

[18] Manetti, p.42, l.150-57: ‘Ed è piu forte, che non si sa, se que dipintorj di centinaia d’annj indietro … se lo sapeuano e se lo feciono con ragione. Ma se pure lo feciono con regola … chi lo potesse insegniare alluj, era morto di centinaia d’anni, e iscritto non si truoua, e se si truoua, non e intesu. Ma la sua industria e sottiglieza o ella la rirtuouo o ella ne fu inuentrice.’

[19] Manetti, p.52, l.345-7: ‘E vide e medito molte belle cose, che da quel tenpo antico innanzi che furono que buonj maestrj in qua non s’erano uedute per altrj che se ne auessi notitia.’

[20] Manetti (p.53, l.358-67) records, but does not explain the function of the strips of parchment upon which Brunelleschi registered heights of structures with numbers and characters during his survey of Roman ruins. It is tempting to think that at a future stage, these calibrations would be transferred to the edges of a picture plane and would somehow generate a measured perspective of the ancient structure.

[21] Orlandi, L’Architettura, I,9. p.69,

[22]Grayson, III, De pictura, p.11, para 1

[23] Op.cit., p.87, para 48

[24] Op.cit., p.107, para 63

[25] Leonis Baptistae Alberti, De equo animante, testo latino, introduzione e note a cura di Cecil Grayson, Revisione generale a cura di Franceco Furlan, Albertiana, 1999, Vol.II, Section 15, p.232ff

[26] Leon Battista Alberti, I Libri della Famiglia, a cura di Ruggiero Romano e Alberti Tenenti; Nuova edizione a cura di Franceco Furlan, Einaudi: Torino, 1994p.101-2, l.21-2: he would like to hear more on the subject of amicizia, ‘quali cominciasti ad amplificare con altro ordine e con altro piacevolissimo modo che a me non pare soleano gli antichi scrittori.’

[27] Romano, Tenenti, Furlan, p.349, l.741-3

[28] Romano, Tenenti, Furlan, p.353-54, l.849-857: ‘Ne io a te negherei, Lionardo, e’ precetti antiqui assai essere utilissimi, ne pero to conceredro che in questo artificio siano quanto vi desidero scrittori molto copiosi; gia che oggi, come tu sai, troviamo in questa materia de’ nostri scrittori non molti piu che solo Cicerone, e in qualche epsitola Seneca; e de’ Greci hanno Aristotele, Luciano. E questi non li biasimo, ma ne molto in questa parte credo altri che io gli lodassi, a cui sempre qualunque scrittore fu in reverenza e ammirazione.’

[29] Romano, Tenenti, Furlan, p.373, l.1369-70

[30] Romano, Tenenti, Furlan, p.417, l.2543

[31] My Albertiana piece [get]

[32]Rykwert et al, VII, 4, p.196; Orlandi, L’Architettura, p. 549: ‘Templi partes sunt porticus et cella interior…’

[33] Alberti, De re aedificatoria, VIII,9

[34] Tavernor [get], Braghirolli or Gaye?